Webb links Enceladus to panspermia

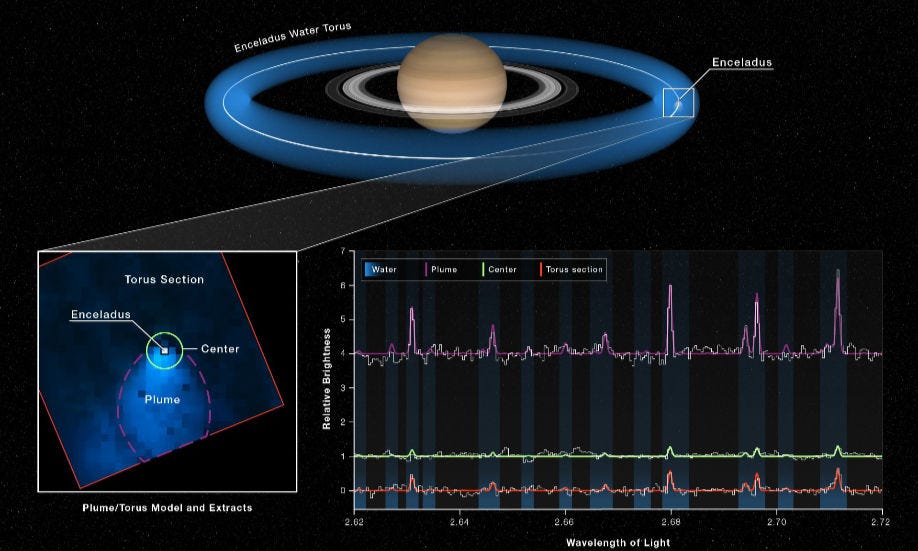

A colossal plume of water vapour has been detected coming from Enceladus, a wee moon of Saturn, according to NASA's James Webb Space Telescope.

Water expelled from Enceladus may be having a significant impact on the surrounding environment, as well as reaching other celestial bodies within Saturn's system.

In the past, Enceladus was known to have water vapour plumes, but this new discovery is truly astounding because this plume extends more than 9,600 km into spacekilometers above the surface and is several hundred kilometers wide. Water is being released in a staggering quantity from Enceladus, raising questions about its composition and its source.

Implications for Panspermia

Intriguingly, the detection of water vapour on Enceladus suggests that the water expelled from its icy surface is not confined within its icy crust but is instead being actively released and dispersed into the wider environment, raising the possibility of panspermia, the hypothesis that life can travel and seed across planets and moons.

While Webb’s data only confirms water vapour dispersal, it raises an intriguing possibility. If Enceladus is spraying life’s building blocks into space, then Saturn’s system may serve as a natural laboratory for panspermia—just food for thought.

The possibility of life-sustaining elements being dispersed into the wider environment is intriguing, even though Enceladus has no definitive proof of life. Water vapour, organic compounds, and organic molecules found by Cassini indicate that the building blocks of life may be transported to other celestial bodies in Saturn's system.

We are, of course, speculating here. As of yet, there is no definitive proof that life exists on Enceladus or else where. Yet, the possibility that life-sustaining elements from this moon might be dispersing into the wider environment presents an exciting prospect for further research.

What we ought to consider is that this discovery demonstrates that water from Enceladus can travel vast distances, an essential aspect of the panspermia hypothesis.

Although we have not yet found life in this water, the fact that such material can disperse throughout Saturn's system provides a critical pathway for potentially spreading life across space.

For panspermia to occur, several essential elements are required.

First, there must be a source of life-sustaining elements, such as water and organic compounds, which Enceladus provides through its water vapor plumes.

Second, there must be a mechanism for dispersal, which is demonstrated by the ability of this material to travel vast distances within Saturn's system.

Lastly, there must be a destination where these elements can potentially seed and support life, which raises intriguing questions about the possibility of life on other celestial bodies. Titan?

The wee moon may be an example of panspermia in action... This is just some pondering, we'll have to wait and see if we find life with future missions.

Life is not necessary for panspermia

Abiogenesis

Along with the transportation of living organisms, panspermia also entails the transfer of non-living materials that could contribute to the development of life.

In panspermia, not just living organisms but also organic molecules and water could travel between moons, planets and solar systems, potentially seeding life elsewhere.

All the components needed for life are present throughout space, so life isn't essential for the hypothesis because abiogenesis (the evolution of life from non-living matter) can occur in suitable environments. Even so, it would be beneficial to start the process from living matter instead of starting from non-living matter.

Is life inevitable?

Maybe life only exists on Earth? I’m not sure about you, but I doubt that, given that there are trillions of galaxies in the cosmos. Here's the cosmic webb just to put that into perspective.

Another great theory is by Jermery English, who believes life is physics, facilitating entropy. Try saying that fast…

“life is facilitating entropy.”

It’s a brilliant wee hypothesis which we’ll briefly glance at.

It proposes that life emerges from the natural tendency of systems to increase entropy.

It might seem counterintuitive, but England argues that some systems, like living things, can organize themselves to better dissipate energy (often in the form of heat) into their environment.

Given that the universe is governed by physics, life arises inevitably, especially at Enceladus. But that’s if the hypothesis is true. You can read the paper here.